Losing Pounds to Win Big: A Pathway to Freedom

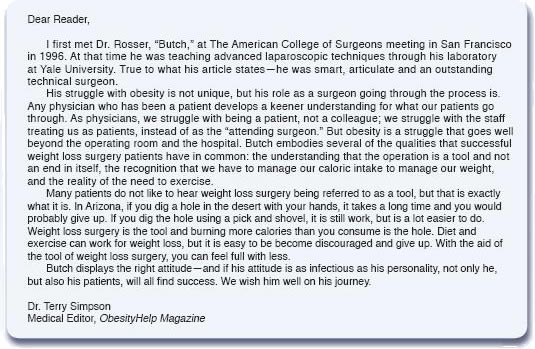

by James "Butch" Rosser, Jr. MD, FACS

by James "Butch" Rosser, Jr. MD, FACS

Obesity has now entrenched itself as one of the most urgent healthcare issues facing industrialized world. Today, more than 50 percent of American adults are overweight or obese, and five to ten million of them are considered morbidly obese. Although obesity rates are higher in African American, Hispanic and Native American communities, obesity can affect anyone. The Office of the Surgeon General reports that it is responsible for as many as 300,000 premature deaths each year. Obesity?s complex etiology includes genetic, neuroendocrine, and environmental causes. Given its pandemic nature, it should come as no surprise that morbid obesity can be a personal challenge for physicians, just as it is for the public. Doctors can occupy the same maximum-security prison as others who suffer with this disease, shackled in chains secured by the sheer magnitude of size and in virtual social lock down as to what life has to offer. This article seeks to portray the issues and challenges of the morbidly obese that seek surgical treatment from the unique vantage point of a surgeon who became a patient.

My search for a solution to my morbid obesity began when I emerged from my mother?s womb. The first child born to James and Marjorie Rosser of the plantation town of Rome, Mississippi, I was ten pounds of crying, hungry baby boy from day one. My parents were particularly proud that their son was ?fat and fine.? Against this social backdrop, it was thought that being above average weight as a child was a good thing. The data that we have today was not generally known or reported back then; now we know that children who are obese at a young age frequently become morbidly obese adults.

During my childhood in Moorhead, Mississippi, my challenge with weight was not a hindrance. Instead, I was considered special and always had women and older girls pinching my ?chubby? cheeks and saying how cute I was. Because of my different appearance, I always got a lot of attention. But the admiration was short lived. When I began elementary school, my aberrant size made me an easy target for the type of vicious attacks that only children can deliver. I tried to overcome these social challenges by being smarter, stronger, faster, wittier, and more articulate than all the others. Despite becoming a superior student and athlete, a great speaker and a leader among peers, the cloak of being ?nutritionally challenged? clung to me like a cotton t-shirt in the heat of a Mississippi summer. You could hear the echoes of criticisms. ?He is an honor student, but?? or ?At six foot four inches and 285 pounds, he is a great athlete with 50 colleges seeking his attendance at their university, but?? I chose to drown out the ?buts? with achievements, and for many years I powered my way through my concerns.

In medical school I was not involved in as much physical activity, and control of my weight became an issue. At the beginning of my senior year, I got on a scale one day and it read 341. Concerned, my wife and I sought the council of a nutritionist. In addition, I increased my exercise regiment and began working out for the first time since I stopped playing football. Over six months I lost about thirty pounds. The crowning glory came when I went back to my high school and spoke at the athletic banquet and I was able to wear a suit that I had purchased as a senior in high school.

Now, I was poised to begin my professional career as a ?lean, mean healing machine?. But, something happened on my way to physical fitness bliss: I began my surgical residency, which presented a brand new level of challenge and stress. At Akron General Medical Center in Akron, Ohio, I got a superior level of surgical training and career nurturing. But I also had the double-edged sword of access to free food twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. I gained back all the weight I had lost, and then some.

About the same time, I began to feel the initial probing of the ravages of obesity related co-morbidities. When I sat or drove for a long period of time, I would develop left knee and ankle pain. And snoring, something I had always contended with, stepped up to extraterrestrial intensity. Previously, it had been just a source of social etiquette lapses and personal embarrassment, but, during my residency, I noticed that I did not feel as rested after sleeping. This fatigue was the first sign of sleep apnea. Despite these challenges, I continued to be productive. At the end of my residency, I probably weighed 360 pounds. I say ?probably,? because I refused to get on a scale. I knew there was problem, but I did not want to know how bad it was. The inflationary spiral of my weight did not stop. The stress of starting a new practice, maintaining an outlandish global academic pace, and experiencing catastrophic domestic upheaval all contributed to the control of my weight slipping through my grasp.

In 1996, while conducting an advanced minimally invasive surgery course at another hospital, I had to go through the supply delivery area to get to the animal facility. I noticed a heavy-duty warehouse scale that was used to weigh large freight items. I closed my eyes and, for the first time since 1980, sought to see how much I weighed. The scale showed 450 pounds. I was shocked, embarrassed, humbled and angry. On that day, I decided that I would take an aggressive course of action to dethrone my lifelong nemesis.

This decision initiated a parade of dietary adventures that included low-fat, high-fat, ?Atkins this? and ?no Atkins that? weight loss strategies. All of the programs produced the same results: initial mild to moderate weight loss with subsequent weight regain surpassing the pre-diet weight. Despite these successive setbacks, I decided to defer to more aggressive measures. I was determined to beat this problem. I attended Structure House, a ?stay in? facility that establishes lifestyle changes through a structured behavior modification program and individual empowerment through education, along with fitness training, nutrition, and psychological profiling. This was the most uplifting and enlightening period of my life long ordeal. This effort suffered the same fate as all of the others, but what I learned proved invaluable as a foundation for future success.

Still determined, I sought help through a physician-supervised program. I was able to achieve some weight loss, but it was clear after a year that we had achieved sub-optimal results. I was healthier, I was more fit, my quality of life was slightly better, but more had to be done. As I assessed my situation, it became painfully obvious that a surgical weight loss procedure offered the only possibility of a cure.

As a patient, choosing the proper procedure is the first and most important step. After careful review of the literature, I believed, without a doubt, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure to be the gold standard procedure for morbid obesity. It can be reproduced with equal efficacy both traditionally and laparoscopically. Results are durable, and the complication rate is acceptably low in the hands of a well-trained surgeon. Because my body mass index was 58, I was seriously concerned about the amount of weight loss I could expect. It had been documented that patients in the super obese category (like me) experience less weight loss with a gastric bypass than with a standard length bypassed intestinal segment (75 cm). Extending the bypassed segment to 150-250 cm seemed to improve the sustained weight of patients like myself. With that data in mind, I decided to seek a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure with an extended bypass segment.

When choosing a weight loss surgeon, the number of procedures performed and surgeon reputation are important considerations. However, I suggest that the patient be willing to look more deeply than these obvious landmarks. Patients should remember that surgery is the first, not the last, step to recovery. With that in mind, the patient?s selection process must consider the whole surgeon/program package. The program must be one of lifelong commitment on the part of both parties. The surgeon and his or her program go hand-in-hand. The patient cannot afford to become shackled with a ?fire and forget? surgeon, or a bariatric program that only has substance on paper. Unfortunately, there are many surgeons who have performed many cases, have reputations of prominence and are perpetuating yet another vicious hoax on those individuals who have repeatedly been victims of false hopes and promises.

Perhaps the most difficult question patients must ask themselves is whether their surgeon is an advocate for the morbidly obese. Does the surgeon take on this great task for the academic and professional challenge alone? Does this individual have a focused sensitivity to the plight of the ?nutritionally challenged?? There are signs to look for that hint to an advocacy presence. If office personnel allow a 600-pound nutritionally challenged person to stand for prolonged periods of time without offering an opportunity to sit, there may be a problem. If all of the individual chairs in the office or clinic have sides, there may be a sensitivity issue. If the staff works in shirtsleeves in the winter with the heat elevated while the ?nutritionally challenged? patients sweat as if they are in a sauna, there may be some issues that need addressing. Surgeons that would let these conditions persist just may not be sensitive to the plight of their patients. I have a firm belief that patients will be best served if their surgeons carry the banner of advocacy for the morbidly obese.

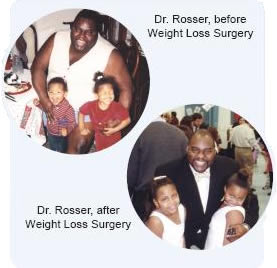

Phil Schauer, my friend at the University of Pittsburgh, performed my surgery. He and his program met all the criteria I insisted be met, and surgery was performed in August 2001. The surgery went according to plan. Fortunately, I was able to have the surgery completed laparoscopically. As soon as I got back from the recovery room, I walked three laps around the ward. I was determined to be one of the best patients on whom he had ever operated.

The first 24 hours were the toughest. I needed my intravenous pain medication pump for pain control. I almost jumped for joy when I got my x-ray the next morning and it did not show a leak. The first liquids in my mouth had the impact of a sirloin steak. However, it was tough to meet my hourly fluid intake goals. In addition, I had to face a ?culinary chaos? phase where no foods or liquids tasted good at all. At this point, it is most important to focus on proper hydration. The extreme frustration that my loved ones and I faced was absolutely overwhelming. This went on for about three to five weeks. Patients must be aware of this challenge and be mentally prepared. I believe the patient goes through a grieving period with separation anxiety generated by losing food as a friend. You may or may not have a drain placed at the time of surgery. Some surgeons place one to warn of leaks. Surgeon preference will dictate whether or not a drain is used. My weight loss has followed the standard pattern for the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: rapid weight loss during the first year with a much slower but steady downward trend over the next 12 months. It has now been three years and three months and I have lost 160 pounds. My co-morbidities have all disappeared and my quality of life has been extraordinarily improved.

The first 24 hours were the toughest. I needed my intravenous pain medication pump for pain control. I almost jumped for joy when I got my x-ray the next morning and it did not show a leak. The first liquids in my mouth had the impact of a sirloin steak. However, it was tough to meet my hourly fluid intake goals. In addition, I had to face a ?culinary chaos? phase where no foods or liquids tasted good at all. At this point, it is most important to focus on proper hydration. The extreme frustration that my loved ones and I faced was absolutely overwhelming. This went on for about three to five weeks. Patients must be aware of this challenge and be mentally prepared. I believe the patient goes through a grieving period with separation anxiety generated by losing food as a friend. You may or may not have a drain placed at the time of surgery. Some surgeons place one to warn of leaks. Surgeon preference will dictate whether or not a drain is used. My weight loss has followed the standard pattern for the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: rapid weight loss during the first year with a much slower but steady downward trend over the next 12 months. It has now been three years and three months and I have lost 160 pounds. My co-morbidities have all disappeared and my quality of life has been extraordinarily improved.

Embracing a surgical solution to my lifelong struggle with obesity brought a three-year sunrise into my life. My improvements in quality of life and co-morbidity management have paralleled that which has been frequently reported. Despite the elation that I feel over my chance for a new lease on life, I would be remiss if I did not touch on current issues that stand in the way of achieving universal access for all in need. Based on my personal experience with the tortuous, ill-defined certification process and lackadaisical pace, along with the lack of a sense of urgency of the healthcare system, I am convinced that the nutritionally challenged face the last bastion of bigotry that exists in this country: size discrimination. There is a deep-rooted ignorance that exists in the public as a whole about the disease of morbid obesity. Unfortunately, this ignorance extends with unabated tenacity into the medical payer and provider community. If a racial or gender based slur were directed toward an individual, the reaction of the general public would be extremely negative. On the other hand, if a fat joke is mentioned, it can be the cause of communal laughter. The message is that it is okay to pick on fat people. I call it the ?Claus perception.? The general public makes the assumption that fat people have chosen to be fat, know that they are fat and are happy being fat, otherwise they would do something about it?as if it is that simple. Societal perception of Santa Claus as fat, helpful and happy causes some people to think that the nutritionally challenged are here to be objects of their personal entertainment. Size insensitive insurance companies and physicians think that this medical condition is the result of self-inflicted self-destructive behavior. The result is that people in need of life-saving intervention are denied access to treatment.

Another hurdle that must be surmounted is the need for and lack of properly trained surgeons who can deliver services with superior outcomes. Up to five percent of the population (about 15 million people) fulfill NIH criteria for surgery. The skill and cognitive abilities that must be possessed to safely execute all bariatric procedures are extraordinary. We face the potential of bariatric complication carnage, if we attempt to use the same education and oversight strategy utilized with the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

In the end, excellent outcomes will dictate the destiny of weight loss surgery. And good outcomes will be intimately linked to cost-effective availability and delivery of postoperative support services. We are now seeing the appearance of ?weight loss surgery refugees,? people who have been operated on and face weight regain challenges without a surgeon-guided program to help them. In response to this problem, I have instituted a ?learning for life? weight loss surgery support group. The support group philosophy is founded on the premise that ?weight loss recovery is a lifetime struggle.? The program is built around a ?triangle of success? that includes psychosocial wellbeing, execution of a sound nutritional strategy, and maintenance of a lifelong fitness program.

The goal is to reach out to the nutritionally challenged community that has chosen a weight loss surgery option and help them make the best of this ?second chance? at life. Support groups that transfer knowledge to outfit the patient for life long trials and tribulations are key to successful weight loss recovery. Every few months, I produce a unique support group format that uses ?edutainment? as an empowerment platform. The group session is more like the Oprah Winfrey Show and features opening monologues, skits, expert guest interviews and advice. In addition, a monthly group meeting is presented in the traditional format to augment this program. Technology-enhanced fitness programs, nutritional advice and support, psychosocial wellbeing, crisis management, and family counseling will discourage weight regain.

Again, the operation is the first and not the last step toward recovery. It is a tool that allows patients to help themselves, but there is a personal responsibility that cannot be delegated to anyone else. In the end, it still boils down to managing the caloric intake/energy expenditure mismatch. Patients must remember that they have been and shall always be nutritionally challenged?successful recovery requires a lifetime of effort.